How many meeting rooms do you need in an office? It’s a simple question, but very difficult to answer. Even experienced architects and designers struggle to incorporate the correct number of meeting spaces, relying mainly on arbitrary rules of thumb and intuition to overcome the lack of empirically verified guidance. Too few meeting spaces make it impossible to reserve a room because they are constantly booked. Too many meeting rooms sit idle and take up space that could have been better designated for another function.

Meeting rooms are a central component of the modern office. On any given day at WeWork you can find our members in meeting rooms pitching potential clients, holding interviews, hosting a lunch and learns, or hashing out the details of their next big idea during a brainstorming session.

With so many important interactions happening every day, we take seriously our role in developing spaces that encourage our members to connect, learn, and grow. WeWork’s Product Research team has been developing methods to predict how often meeting rooms are used.This will allow us to replace the rules of thumb with accurate measures to determine how many spaces we need.

The story of our meeting rooms

In an earlier post, director of research Daniel Davis described WeWork’s unique ability to improve our space by gathering and analyzing member feedback. In our latest round of research we applied a similar methodology to the allocation of meeting spaces.

We analyze how frequently particular meeting rooms are booked by our members. Because we design and manage our spaces, we have access to a lot of examples. We gathered information from more than 800 meeting rooms and examined a variety of space types; everything from a boardroom in London to a screening room in Los Angeles to a conversation room in Shanghai (a room with couches instead of desk chairs).

What we found was that each room tells a story. Some are perpetual favorites—always booked and always highly rated by our members. Other rooms are underused, with few members reserving and using them for meetings. We can take each of these rooms and begin to learn why members book (or don’t book) them, which helps us predict how often our rooms will be booked.

A number of factors help us predict the popularity of a meeting room. Some of them are obvious—companies with fewer employees tend to book meeting rooms more frequently per person than companies with more employees. So a meeting room that’s surrounded by many small offices are booked more often than a meeting room that’s surrounded by one large office.

But finding other relationships can be difficult. Does an employee from a 50-person company book 12-person meeting rooms just as frequently as an employee from a four-person company? What about a four-person meeting room?

Deploying machine learning

To help us understand these relationships, the Product Research team used machine learning to forecast how often meeting rooms would be used. You may have heard of the term machine learning—It’s a concept that has been around for decades, but with the recent rise of significant breakthroughs like self-driving cars and voice-activated assistants, machine-learning has become a much-talked-about subject.

Even with this recent attention, it hasn’t made much of an impact on architectural design, and our application of machine-learning in the evaluation of architectural layouts remains highly novel.

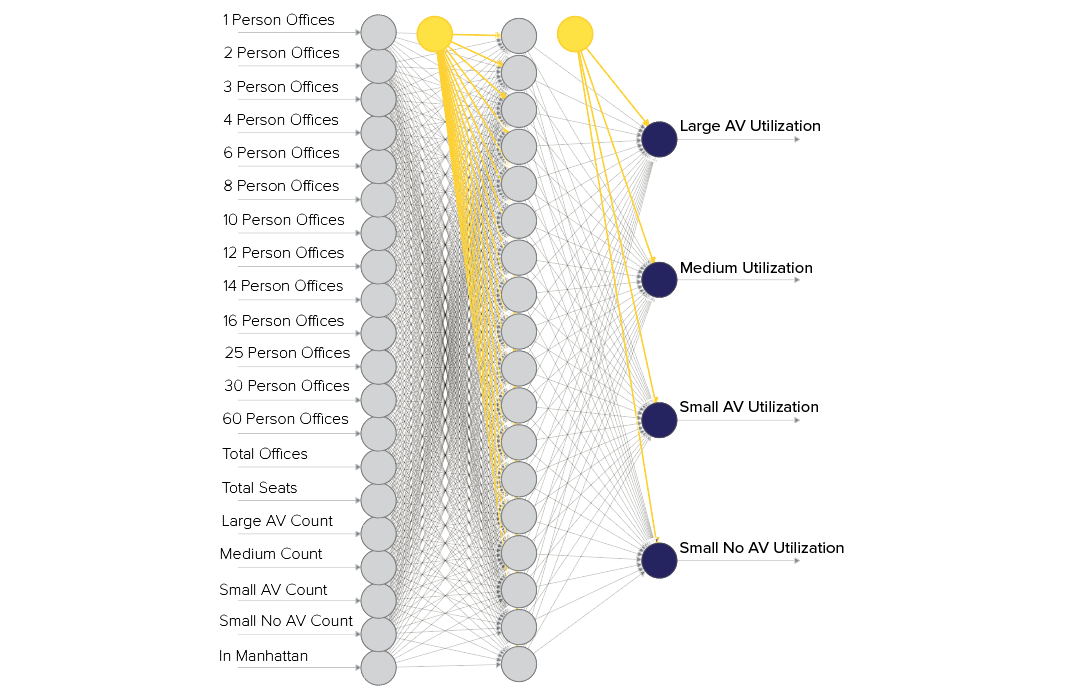

For this project we used an artificial neural network machine learning algorithm. We fed the neural network information about the layouts of our locations (fig. 2), including the number of offices, the size of the offices, the number of meeting rooms, and the facilities in the meeting rooms.

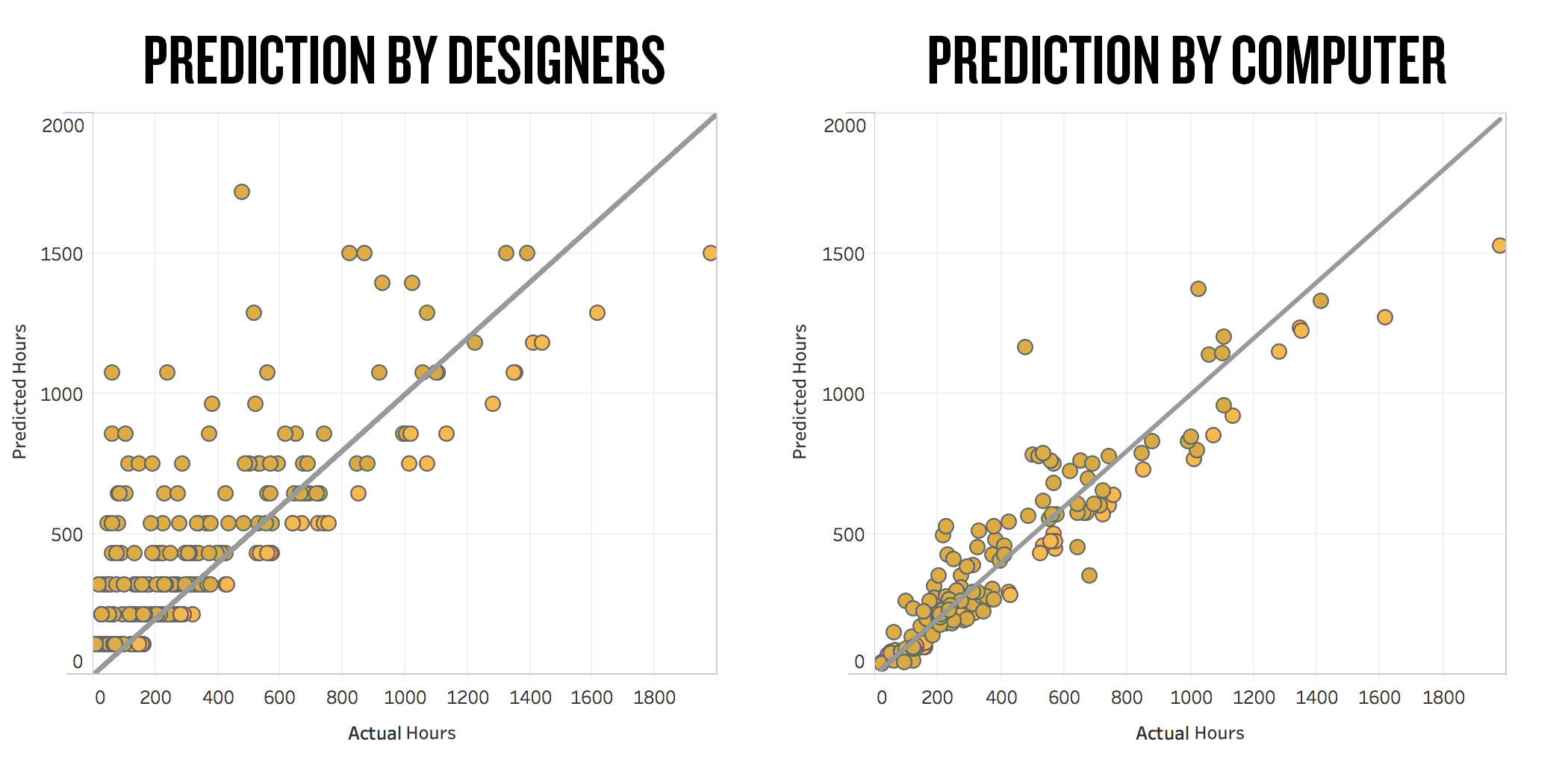

Every time the network was fed a layout, it was also shown how frequently the rooms were used in recent months. Over time, as the network saw the layouts repeatedly, it began to learn the relationship between layout and usage. Eventually it understood this relationship well enough that it could fairly accurately predict how a layout would be used by our members before we began construction.

We put this approach to the test by providing the network with layouts that it had never seen before—ones that we kept hidden during the training. The outcome was surprisingly accurate. We estimate that the neural network is 40% more accurate than human designers in predicting how frequently a meeting room will be used by the building’s occupants.

As we add locations, open in new cultures, and test new layouts, our team will have more data to feed the neural network. This means our predictions of how people use meeting rooms should become increasingly accurate.

The most powerful implication of this study is that before we begin construction, our teams can plan a space that fits the needs of the members who will one day occupy it.

It is a process that can be expanded outside of conference rooms and beyond the design of an office. While nothing will replace the expertise of an architect, powerful new metrics like machine-learning can help guide designers, fueling the efficiency of their creations in the modern age.