We’ve all been in bad meetings. But the hard truth is, a successful meeting isn’t as simple as putting time on a calendar. Our series Meeting Heroes invites you to learn how to save the [work] day with your next gathering. You’ll never have to hear the phrase, “This meeting should have been an email,” again.

We spent the last three years studying the science of emotions and their intersection with our lives at work for our book. Many of the questions we received were about—you guessed it—how to handle disagreements with colleagues.

There are two different kinds of conflict: task conflict (the clash of creative ideas) and relationship conflict (personality-driven arguments). Task and relationship conflict are often related—it’s hard not to take disagreement over ideas personally. Here are some tips on how to resolve each type of conflict.

Task conflict

The two of us are not immune to creative clashes—we often dealt with task conflict while writing our book. Mollie likes to quickly write an initial draft and send it to our editor for immediate feedback, while Liz prefers to mull over sections and send our editor a more polished version. Over time, we realized this difference is useful: Liz ensures we don’t send out a half-baked chapter, and Mollie prevents Liz from overly obsessing over syntax. We learned to find a healthy tension by talking through why we do or don’t feel ready to hand over a chapter.

There are many ways teams can create structures that encourage productive task conflict. For example, every morning during Pixar dailies (daily reviews of draft films), animators look at one another’s partially completed frames and propose edits to the motion, body, and facial expression of the characters. Participants are encouraged to make all comments about the shot, not the animator.

To avoid task conflict, some teams conduct a blameless post-mortem, gathering at the end of a project to review any issues that came up during the process. Team members can share their actions, what effects their actions had, what assumptions they made—all without fear of punishment or retribution.

Relationship conflict

Let’s go back to our conflict about whether or not to turn in a chapter draft. If Liz had at any point said to Mollie, “It’s a dumb idea to send this chapter to our editor now,” and Mollie responded with, “You never take my suggestions seriously,” what started out as task conflict would have devolved into relationship conflict.

It’s easy to write relationship conflict off as a clear-cut case of irreconcilable differences, but it can often be resolved simply by hearing each other out. For example, you’re probably either a Seeker—you like to argue—or an Avoider—you’d rather eat a slug than deal with confrontation. These two types run into problems when Seekers engage in ritual opposition, a form of verbal one-upmanship aimed at testing ideas (see: “How did you not think of…”, “That suggestion makes no sense,” or simply “You’re wrong”).

To avoid hurt feelings between Seekers and Avoiders, when you first start working together, discuss each person’s conversational style and then decide how the team will handle conflict. Is it OK to immediately and aggressively poke holes in someone’s idea, or should criticism be delivered more indirectly? In the moments when you’re not able to sidestep clashes between these two types, Avoiders should remember that Seekers don’t intend their comments as personal attacks or insults. And Seekers should remind themselves that confrontational debate might shut down input from others.

While it’s unlikely that an Avoider will have a conflict with another Avoider, if that happens, one of you will likely need to bite the bullet and face the conflict: Acknowledge to the other person that neither of you likes conflict, but it’s best to address it. If two Seekers are fighting, you may hear raised voices. The Seekers should try to remember that no one is going to win the conversation, and seek peace as an outcome.

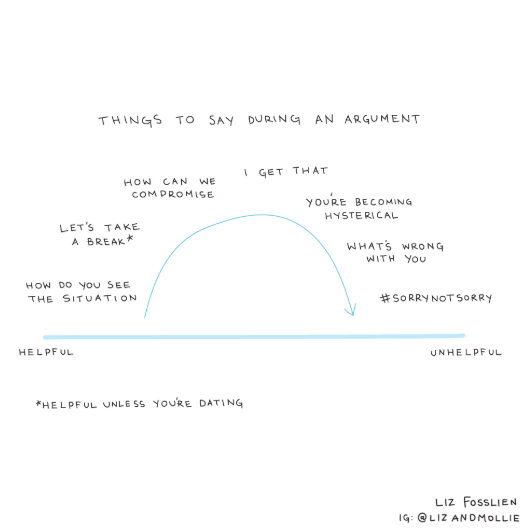

How to fight a good fight:

- Write a user manual. The best way to navigate potential conflict is to preemptively create structures that help communicate preferences and work styles. Many of the CEOs interviewed by New York Times columnist Adam Bryant create “user manuals” or “how to work with me” guides to make collaboration easier. These help you reflect on your work styles and share them with others so they can understand you better. To achieve the same with your team, we’ve created a user manual template on our website. Download the template, have everyone on the team fill one out, and then share them with one another.

- Conduct pre- and post-mortems. Set aside half an hour at the outset of a project and have team members list everything they fear might go wrong. This allows the team to fully understand and address potential risks. If you had conflict during a project, schedule time after the work is done to figure out what could have gone better and why—and brainstorm how you can avoid these issues in the future.

- Invite structured criticism. A great way to make critiques generative is to ask people to share ideas that are either 1) quick fixes, 2) small steps that make a meaningful impact, or 3) a way to rethink the entire thing. These buckets add helpful constraints and make the conversation less likely to devolve into personal attacks.

- Find a conflict role model. We all know someone, personally or professionally, who tells it like it is, but in a way that is helpful. Next time you’re around this person, observe how they act, and try to model your behavior after theirs.