Your roommate, sister, or Hoda Kotb might have already told you about the bullet journal method—a technique for organizing your daily life that’s quickly becoming a phenomenon.

It’s hard to avoid. Ryder Carroll’s system and his accompanying book, The Bullet Journal Method: Track the Past, Order the Present, Design the Future, have thousands of acolytes, and if you search under one of its dozens of hashtags (there are 3.2 million posts on Instagram for #bulletjournal alone), you will see perfect journals on tables (with mugs of matcha tea next to them) containing neatly lettered entries, spotless schedules, and ebullient phrases like “INSPO!” and “A lot can happen in a day!” in swirly cursive.

Perhaps this makes you recoil, like it did to me. Images of perfection cause me to experience the same cloud of hate/envy/lust that forms when I (foolishly) scroll through @HotDudesWithDogs. My body will never look like that, and my notebooks won’t either.

What is the bullet journal method?

The Bullet Journal Method is, essentially, a system of organization to help you deal with your daily pile of tasks by way of handwriting in a specific format in a dedicated notebook. The method stresses that it must be done by hand, writing and recording daily activities, again and again, day by day. It’s a natural filtering system that allows you to see what’s important and what is wasting your time.

“The whole idea is to clear the clutter: Take all of the things we put in our scattered little minds, all the pieces of paper, and have a one-stop resource,” says Magdalyn Duffie, a freelance graphic designer in North Carolina who started bullet journaling a year ago in an effort to exercise more and drink more water. “It’s been good to see when I did well and when I fell off. Also, it’s for good accountability, like, ‘Drink your water, girl!’

Duffie taught an introductory workshop on bullet journaling at Raleigh’s WeWork One City Center. They had slots for 50 people, but 125 signed up. She says the hardest part for people to absorb was the larger theme of intention setting. “The practice of taking a moment in the morning and thinking about the day ahead, that’s what is really hard for people,” she says.

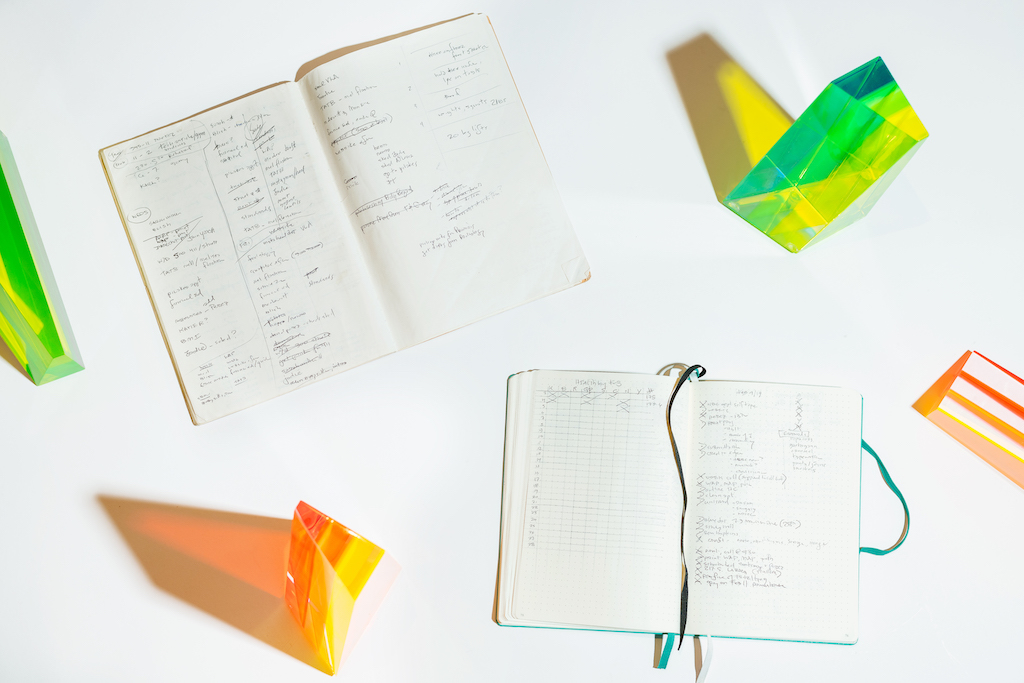

Unfortunately, I didn’t have Duffie as a guide, just an assignment to test-drive the method and declutter my notebook. My first problem: I don’t have just one notebook. I have my weekly planner, my pocket notebook, my thin Muji notebook for daily to-do lists, ideas, and meetings, and a large Leuchtturm1917, which I think might be my 100th diary. All of these books are unruly, wildly varied, with papers and Post-Its, and documents sticking out of them. I don’t need another notebook, I thought. Still, I bought an official Bullet Journal branded notebook (also by Leuchtturm1917) and Carroll’s book.

Carroll, who was a digital product designer before he popularized paper planners, guides you through the method in his book like your patient, mild-mannered nephew. The format can seem dizzying at first.

How to bullet journal

Opening your book, you leave the first few pages blank. At the start of a month, you write down the dates in a column, with a brief note beside important upcoming dates, and on the opposite page, a list of tasks you have to accomplish for the week. This is your Monthly Log.

Then, you take a two-page spread and divide it into six sections, labeling each for the upcoming six months, writing in upcoming events and deadlines. This is your Future Log.

On another page, you write down today’s to-do list. There are specific symbols for this list—a dot for a task, a circle for an event, a forward arrow to roll it over to the next day, and an X for completion. Carroll calls this “migration.” “Migration is designed to add the friction you need to slow down, step back, and consider the things you task yourself with.”

I like this term. As a person with a million things to do, I’ve been “migrating” for years but had been calling it “procrastination,” “laziness,” and “failure.” A few days into the process I was beginning to see the benefits of calling it something nobler, weeding out what is important and what isn’t.

There is also a dash symbol to use for “notes”—observations, reflections, recommendations—and an exclamation point for sudden ideas that don’t fit in other categories. If these notes start taking up more room, or a task gets more complicated, they can be grouped and moved to other pages in your notebook, called “Collections.”

These collections formed immediately for me—notes I had on my desk of movies I’ve wanted to watch became a “Movies” page. A recording device my friend suggested went in “Tech,” and I even created a “Karaoke Songs” list. This process also helped me consolidate some projects, including an upcoming trip to Los Angeles, a log of daily exercise and meditation, and a page tracking the submissions (and rejections) of a novel I am trying to get published.

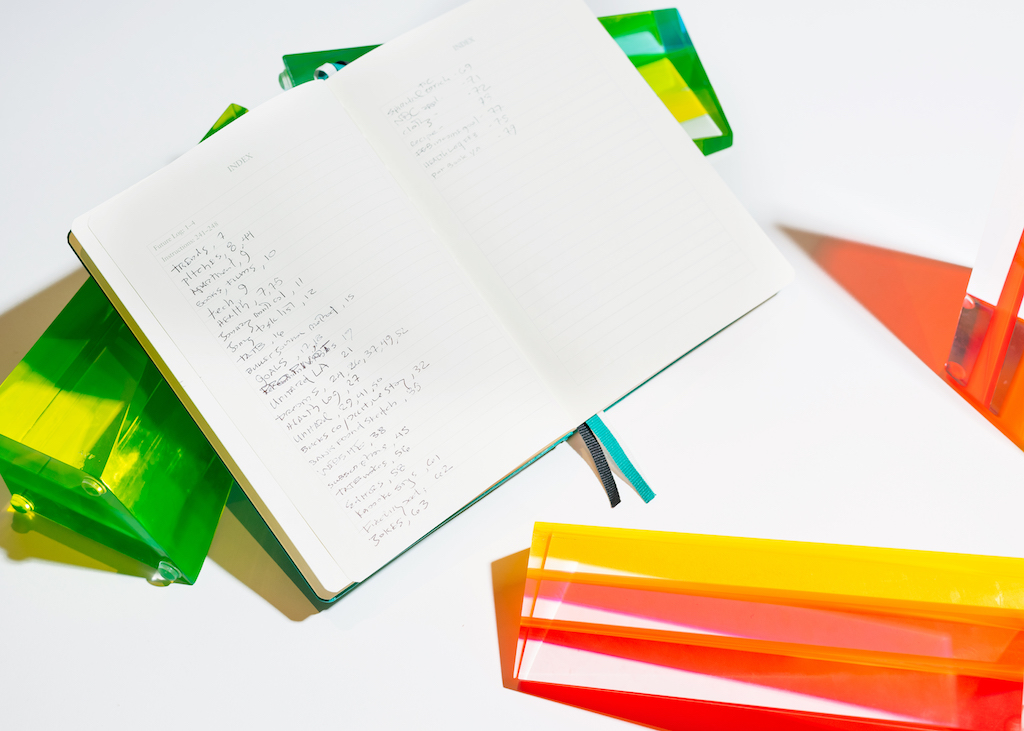

Carroll solves the problem of locating all these collections by devoting those first blank pages of your journal to an “Index.” Once you give a page to a certain topic, you write down the title and page number in the index at the beginning of your book. So, my daily to-do lists are interrupted by “Collections” for a trip to L.A., my Health Log, books to read, etc., and this is OK because the index in the front puts everything in order. This may be game-changing for me. The piles of spirals I kept over the years are full of thoughts I’d only see if I spent time going through them, trying to decipher my handwriting.

The “dash” and “!” have also been revelatory. The freedom to include personal thoughts on my to-do list page has allowed me to record mundanities and smaller moments that sometimes go missing in my diary. Over the past two weeks, I recorded how I felt a little “off” after a recent comedy gig but still had fun; a dream where I was a fugitive on the run with Gillian Anderson; and the observation that I went out with a friend, spent the whole time gossiping about other friends, and then felt bad about it.

At the end of the month, Carroll asks you to go through your log and reflect on your life to get a granular look at how you use your time and what occupies your mind. If something on your task list is lurking there, unfinished for days and weeks, you have the freedom to cross it out and release it from your life.

Does bullet journaling work?

One night in the middle of my bullet journal test drive, I watched Marie Kondo’s Netflix show Tidying Up with Marie Kondo. In her kind way, she encouraged a young family to properly fold their clothes, taking time to touch each item and thank it for its service. I got out my BuJo, added “fold laundry” to my daily log, sat on the floor, and folded my clothes. Touching each one, I thanked them. As I folded a pair of brown corduroys I have had forever, tearful appreciation gushed out of me.

Like Kondo’s, Carroll’s approach is comfortable and kind. He asks you to try this with care, gratitude, and a sense of relaxation. “No, this is not some dubious invitation to worship this methodology. It means that you no longer have to wonder where your thoughts live.”

This technique is, in a way, a left-braining of the right brain, and I am not sure yet if it can be used artistically. My ideas come suddenly and fleetingly and can’t wait for me to thumb through, find a designated page, and write it down neatly. (“You could make a ‘mind dump” section in your book,” suggests Duffie.)

If anything, it has transformed my to-do list. The design heightens the satisfaction of crossing something off. And, like my beloved brown corduroys, I have never realized how important my to-do list is. I now have respect and gratitude for it, and the result is that it looks better, happier, like I gave it a makeover and haircut. Just two weeks in, this is already engendering more respect for my time, my ideas, and where they should live. Also, my closet looks amazing.

Three things to know about bullet journaling

- Swirly cursive and Insta-ready doodling are not required. Carroll downplays all the Instagram inspo, assuring you that “the only thing that matters in BuJo is the content, not the presentation. If you can elevate both, then my hat’s off to you. But the only artistic skill required is the ability to draw straightish lines.”

- Be prepared for a three-month commitment. Carroll makes clear that the method is different for different people, and that you may eventually customize it to your own life. But he does ask that you to try to stick to the format initially for three months before you toss it aside or transform it.

- Write down everything. “Good or bad, big or small, jot it down,” advises Carroll. “If we operate on memory, we’re apt to repeat our mistakes by fooling ourselves into believing that something had an effect when it actually did not.”

Mike Albo is an American writer, comedian, actor, and humorist.

Rethinking your workspace?