Have you ever noticed that some people are consistently luckier than others? They run into just the right people at just the right time, people help them out, and they get free things more often than they should. As a result, these kinds of people end up being much more successful in life. So what’s the deal?

I recently had a conversation with a friend who brought up the idea of “designed serendipity.” He says that even though serendipity is when good things happen by chance, if you work hard enough you can almost guarantee that they will happen.

This seems impossible. If luck and serendipity are inherently random, how can you guarantee that they will happen?

Consider the case of lottery tickets. Sure, the chance of winning a lottery may be one in a million, but if you buy one million lottery tickets, then you can almost guarantee that you will win. (I don’t actually encourage this strategy—for various other practical reasons.)

The general idea is: if you put yourself in many situations where you can get lucky, the equivalent of buying a bunch of lottery tickets, you’ll probably get lucky.

(And, as my friend Mathias Vestergaard notes, “If you consistently avoid being in situations where you can get lucky then you will certainly never be.”)

How this actually translates into behavior will depend on the context. I’m going to talk a little bit about serendipity in startups and business, since it’s the area I’ve been thinking most about recently.

Over the summer my company (One Month) participated in Y Combinator, a startup accelerator program. The stated goal there was to grow at least 10 to 20 percent (either users or revenue) every week for three months.

This is really easy at first?—?because you have such small numbers to begin with. When you only have 100 users, it’s not hard to get another 20. You do a quick Facebook post asking all your friends to join. Congratulations, you grew 20 percent this week.

So the first few weeks are easy because there’s so much low-hanging fruit –optimize your landing page a little, start a blog, send out a newsletter email, and you’re good to go.

But each week it gets harder. Not only are you setting a higher bar for yourself each week, but you’re also exhausting most of your opportunities.

That’s where serendipity comes in.

In order to be successful, you have to learn how to create your own luck.

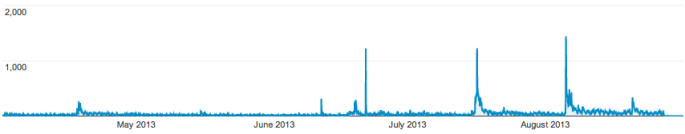

At One Month, we managed to hit our growth goals week after week, but just barely.

In July, it happened because a friend wrote a blog post on the LinkedIn Influencer Network about why everyone should learn how to code, and he gave a nice shoutout to One Month Rails. 80,000 people read that post, and it single-handedly got us over 250 signups.

Then in August we got featured in TechCrunch and got a whopping 1200 signups in 5 days.

It’s easy to look back and take for granted the fact that we got lucky. To forget all the incredibly hard work and sleepless nights that got us there. The thing is that we almost didn’t make it.

I never asked my friend to write that LinkedIn post?—?but I did send him an email asking for introductions to people at TechCrunch, Mashable, or Wired that could write about us. In fact, I almost didn’t want him to write his post because I wanted to get an exclusive feature on a bigger site. Thankfully he did it anyway?—?and so we randomly woke up one morning and had more signups by 8am than we had the entire week before.

We’ve been conditioned to think that successful startups grow with a beautiful, curvy, hockey-stick shaped curve:

But that’s not how it works. Growth is ugly, hard work, and it comes in spurts, with blissful highs and painful lows.

So how can you make success as likely as possible?

I think of it as setting thousands of little serendipity bombs.

Serendipity bombs are little packets of potential opportunity that you create by writing an email to a friend, by going to a conference, by calling up your most active user, by experimenting with a new feature, or in any number of different way.

And they’re bad bombs because most of them fizzle before they ever have the opportunity to go off. Still, if you set enough of them, the odds slowly start to sway in your favor.

I suspect that the same is true for individuals, and creativity as well (though that’s a topic I don’t know enough about). What kind of behaviors can you do that will make it more likely that you’ll get lucky?

Here are a few that I do, and I invite you to suggest others:

- Be open to meeting new people, especially other people who consistently get “lucky.” This is especially true if they don’t seem helpful to you or what you’re doing right at that moment. Luck is almost never obvious. Be nice to people. Don’t work alone at your office all day long. Spend some time each day sitting in a coffee shop. Talk to five new people a day. If you’re shy, start by just waving.

- Follow up with people when you do meet them, and explore potential opportunity further than most people would. Make sure to leave every conversation with something to follow-up about. Then get their email and follow-up within 24 hours. Hang out with people you normally wouldn’t hang out with. Try a new group activity at least once a month (like improv comedy, creative writing, rock climbing, or dance lessons). Put yourself out there emotionally. Do good things for other people. And don’t be afraid to be vulnerable.

- Don’t be too focused on one thing or one approach. Let yourself get creative. Allocate at least some time for different approaches to things you’re currently doing. After Steve Jobs dropped out of college, he sat in on a calligraphy class that he had always wanted to take but never had a good excuse to. Jobs later said, “If I had never dropped in on that single calligraphy course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts.” I love that.

Try to design serendipity into your life and then don’t get angry when people see it as luck and ignore all the hard work you’ve put into it.

I’d love to hear other serendipity-designing techniques and stories of serendipity you have.

Thanks to Cody Brown, Chris Castiglione, Jake Heller, Daniel Karpantschof, Susan Kish, Scott Klein, Nikhil Nirmel, and Mathias Vestergaard for reading drafts of this.

Editor’s note: This story originally appeared here.