Years can pass between the design of a building and its eventual inhabitation.

It takes so long to construct a building that the designers often move on to their next project, or the project after that. They may return to the building for an opening ceremony, but typically they have little incentive to hang around and learn whether their design was effective. It’s not like they can change the building once it’s built.

If you could meet the person who designed your building, what would you tell them? The designers probably don’t know that your office overheats in the afternoon sun or that they didn’t include enough space to eat during lunch. Chances are they haven’t visited, haven’t asked your opinion, and haven’t studied how you use the space. They don’t know which elements of the design work and which ones don’t.

Architect and theorist Frank Duffy writes in Work and the City (2008) that the disconnect between architects and inhabitants is possibly due to the building industry’s economic incentives to tear down old buildings in order to get paid to erect new ones. Because architects are so focused on new buildings, Duffy says that “architects have little motivation to measure and hence no vocabulary to describe how efficiently office buildings are occupied over time. Because our heuristic seems to be ‘Never look back,’ we are unable to predict the longer-term consequences of what we design.”

When you consider that buildings cost millions of dollars, consume vast resources, and greatly impact our overall happiness and productivity, it is crazy that designers so rarely return to their projects to learn from past mistakes and successes. Instead, architectural design is mostly based on intuition rather than an empirical understanding of whether it will positively impact the building’s eventual inhabitants.

A few of the best designers study their past projects. They return to old buildings to survey inhabitants, monitor energy usage, and observe people using the space. But even the best, most enlightened firms can’t do this very often because building owners don’t want the architect returning every year to run a series of tests. And even if firms could return, insights from one project don’t always apply to the next, particularly if the context is different—studying an office in Shanghai probably tells you very little about how to design an office for a company in Silicon Valley.

Learning from WeWork

At WeWork we are obsessed with creating the best environment for our members. We want people to feel excited about going to work everyday, and we want them to go home feeling fulfilled. We think we can achieve this partly because we can do something that very few architects get to do: We can talk to the people who use our spaces.

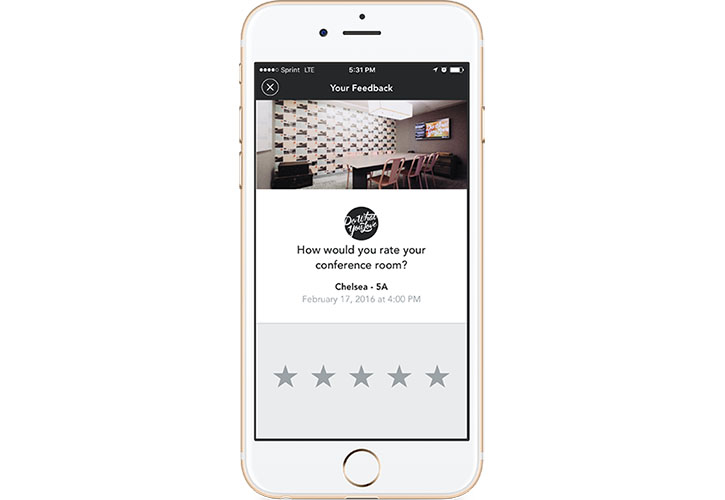

We spend a lot of time listening to members, asking them questions, and analyzing their feedback. After a member uses a conference room, for instance, a screen pops up on the WeWork app asking them to rate their experience in the room—much like how you would rate a ride with Uber. This feedback is immediately sent to the building’s community manager, which allows our teams to quickly remedy any urgent problems, such as missing whiteboard markers.

The value of the feedback does not end there. We also send a daily summary of the feedback to WeWork’s designers and executives, which gives them an overview of how the rooms are performing that day.

Imagine being a designer and getting an email every day containing feedback from people who have used a conference room you’ve designed: Every day you read about the acoustics and the furniture you specified; every day you hear directly from the people you are designing for. Over time you develop an empathy that makes you acutely aware of how your designs impact the people who inhabit them. It is a level of feedback that is virtually nonexistent in the rest of the architecture industry.

Spatial Analytics

There are obviously many factors that determine the success of a building, some of them quantifiable, some of them not. Recently, we’ve expanded our effort to understand our buildings by starting to tease out these factors in a process we’ve termed Spatial Analytics.

At the moment we have a portfolio of approximately 50 open buildings (soon to be many more!). Despite being organized and designed differently at every location, each building contains similar elements: All have offices, lounges, and other components that are common to a WeWork space. These commonalities allow us to compare buildings to see whether those with large lounges foster better communities or whether buildings with more phone booths have fewer noise complaints.

In parallel to these comparative studies, we are also carefully observing how members use WeWork buildings.

To give one example from this research, we have been analyzing the size of meetings in the conference rooms. In other words, what is the average size of a meeting in a four-person conference room? In a six-person room? In a 12?

Your intuition might be that a four-person room tends to have four people in it, and a 12-person room tends to have 12 people in it. Before this research, that was my intuition.

The WeWork Research & Development (R&D) team has spent considerable time walking through buildings, counting the number of people in conference rooms. We now know that the average meeting involves just two or three people—regardless of room capacity. Take a look the next time you are walking through a building. Perhaps you can spot the pattern if you know what to look for, but it’s unlikely you would intuitively think that a 12-person conference room tends to be occupied by just two or three people.

For our designers, this type of insight sparks all sorts of ideas about how we could improve the meeting experience at WeWork.

As WeWork grows, we believe there’s value in investing time to listen to our members and analyze our buildings. It is something that almost no architect can do, and it is something we hope will differentiate the quality of design and experience at WeWork locations.

To learn more about Spatial Analytics at WeWork, check out Daniel’s keynote at the Design Modelling Symposium.